Iot in Arts and Cultur in Camsrt Cities Exmaples

1. Introduction

The shifting discourse on Smart Cities abroad from "smart" applied science alone towards centering on humans on 1 hand, and the ascension of the Creative Cities on the other, offers new perspectives on the development of cultural activities in the city. This commodity explores the convergence of Smart Cities and Artistic Cities toward a new nexus of Smart-Cultural Cities. It frames the chief actors on the governmental, industrial, academic and creative person levels that currently contribute to the discourse on both Smart Cities and Artistic Cities in Singapore and delineates areas of convergence of both concepts, positioning fields of current and future operations and possible entry points in this discourse.

The enquiry questions of this paper are the post-obit:

-

Do smart technologies that bulldoze Smart Cities and creative economies that occur in Creative Cities give ascension to the new Smart-Cultural Cities nexus?

-

Can network assay assistance formalize the relationships amidst actors of Smart-Cultural Cities?

-

Can we identify meaningful groups of actors within the Smart-Cultural City of Singapore?

The article is structured equally follows: Section ane discusses the evolution and evolving definitions of Smart Cities to determine what makes Singapore a Smart City. It then introduces Creative Cities as a planning paradigm. A table illustrates what makes Singapore a Creative City, Creative State, and Creative Nation. The section concludes by discussing the convergence of Smart Cities and Creative Cities. Section 2 introduces the database of actors inside this Smart Cities and Creative Cities nexus from authorities, industries, academia, and artists established by the research customs in Singapore. It further describes the methodology of bipartite graphs used to solve a deterministic optimization problem as presented hither. This method is widely used in mathematics and engineering just is a new contribution to the field of digital humanities. Section 3 presents the results of the optimization problem. It reveals three emergent clusters that nosotros interpret as Urban Scenario Makers, Digital Cultural Transformers, and Public Engagers. The cluster interrelations further reveal underlying connections between these clusters. Section four discusses the results by returning to the research questions.

one.ane. Evolving Definitions of Smart Cities

The concept of Smart Cities emerged out of a technologically driven discourse and gradually broadened in scope to embrace a man-centric discourse in the early on 2000s across the globe [1]. In parallel, the calibration of ascertainment and complexity grew from smart devices to smart homes, smart districts, and smart nations. Recent literature reviews [2] on smart cities include topics of governance and smart cities [3], sustainable development and smart cities [4], the part of the Internet of things (IoT) and smart cities [5], and innovation and smart cities [six].

Technological Definition. The concept of Smart Cities can exist traced back to cybernetic thinking of the 1950s that understood circuitous human being-fabricated systems such as cities as sets of elements that interact and that can be regulated [7]. The appearance of computation and the Net fueled these thoughts in the decades that followed. Applied applications emerged in the context of energy efficiency applied to the scale of cities around the end of the 20th century. Around 2000 so-called "smart grids" were proposed as distributed energy networks that could react to dynamic energy demands. The upgrade of conventional to smart grids promised enormous efficiency gains. These smart energy grids were too seen every bit the back-bone of information and communication technologies (ICTs) that could give rise to Smart Cities. As part of the European Strategic Energy Engineering science Plan (SET-PLAN) [8], the European Spousal relationship envisioned the creation of a network of thirty Smart Cities past 2020; these cities, samples of loftier energy efficiency standards, set up some mutual goals, amongst which the minimization of emissions employed in building technologies and transportation, and the better employ of information technologies for the education of free energy-related professional figures [nine]. The term "smart" refers to the potential of systems to automate routines, react faster, process more data, and thus become more than resilient to time to come changes. Rapidly, many aspects of urban infrastructure were identified to get smarter: energy, transport, h2o and waste management, etc. [ten]. Cisco defines smart cities as those who adopt "scalable solutions that have reward of data and communications technology (ICT) to increase efficiencies, reduce costs, and enhance quality of life" [eleven]. Smart cities and smart infrastructure are explored by Pollalis [12]. The initial understanding of "smart" also gave rise to its later critique: a technology-driven definition with mainly economic benefits cannot depict the complexity of urban phenomena alone [13].

Broad Definition. The research framework regarding the Smart Cities turned toward the "utilization of networked infrastructure to amend economic and political efficiency and enable socio, cultural and urban development" [14] and shifted in terms of its content and objectives in 2010 with Giffinger's study to ascertain the "smartness" of medium-sized cities [15]. The written report analyzes 70 European medium-sized cities, referring to six specific characteristics: economy, people, governance, mobility, environment, and liveability. What makes this research methodologically innovative is the interest of additional variables exterior of the energetic sphere, such as governance, participation, and quality of life. The White Paper, produced in 2011 by the Expert Working Group on Smart City Application and Requirements, conspicuously states the need to focus on broader aspects rather than only the technological ones: "The concept of Smart Cities is gaining increasingly loftier importance as a means of making available all the services and applications enabled by ICT to citizens, companies, and authorities that are part of a urban center's organisation. It aims to increase citizens' quality of life and ameliorate the efficiency and quality of the services provided by governing entities and businesses. This perspective requires an integrated vision of a city and of its infrastructures, in all its components, and extends beyond the mere 'digitalisation' of information and advice: it has to contain a number of dimensions that are not related to technology, e.g., the social and political ones" [16]. This broader definition is widely accepted today and understands Smart Cities as a processes rather than a static outcome, "in which increased citizen date, difficult infrastructure, social capital and digital technologies make cities more liveable, resilient and ameliorate able to respond to challenges" [17]. Similar definitions accept been issued past the Bundesverband Smart Cities [eighteen] and the Centre for Cities [nineteen]. Layne and Lee describe the evolution of e-government in iv stages [20]. Mechant and Walravens analyzed the convergence of e-governance and smart cities enabled by new digital technologies leading to "amend-informed decision making and loftier quality services, but assumes far more complex partnerships with very diverse stakeholders, such as large and small companies, civil society, academia, individual citizens and and then on" [21].

Citizen-Focused Definition. It becomes apparent that this broad concept of a Smart City hinges on the inclusion of citizens [22]. A citizen-focused definition has as a foreground the human-centric aspects of cities sided by the ubiquity of mobile devices, the increased production of data, feedback, and response mechanisms. The Future Cities Laboratory at the Singapore-ETH Centre thus adopted the term Responsive City borrowed from Goldsmith and Crawford [23]. This concept places human-centered governance equally its main objective, employing "the responsive, interactive and participatory possibilities of information engineering science" in the center of the discourse [24]. Responsive Cities are human-centered in ii ways: (1) as a goal, which supports social justice and urban quality and is focused on people, rather than applied science, and (2) with respect to governance, planning and design processes, which are noesis- and data-based, transparent, open, and participatory [25]. This definition includes social media information produced by the citizens and gradually completing a picture show of urban activities, interests, and intensities [26]. It further allows us to look at the inclusion of the Cyberspace of things (IoT) from a denizen point of view [27]. This concept of the smart city aims to accomplish the highest quality of urban life [28].

1.two. What Makes Singapore a Smart Metropolis?

Singapore is well positioned to be a smart city and has implemented many aspects of smart city technology and governance [29]. As a metropolis-state, Singapore the smart city is at the same time a smart nation. The smart nation engages with all urban sectors and in particular mobility, wellness, prophylactic, and productivity. Consequently, Singapore ranks loftier on international liveability rankings. Singapore'south smart nation concept is [30]:

-

Guided by "Liveability": "A Smart Nation is one where people are empowered past technology to atomic number 82 meaningful and fulfilled lives."

-

Engineering science-driven: "Through harnessing the ability of networks, data and info-comm technologies, we seek to improve living, create economical opportunity and build a closer community."

-

Embracing denizen-centric governance: "A Smart Nation is built non by Regime, but by all of us—citizens, companies, agencies. This website chronicles some of our endeavours and future directions." [30]

ane.3. Artistic Cities as Planning Image

The Artistic City is a planning paradigm or urban agenda for cities, encouraging the inclusion of culture and creativity equally solutions to urban problems. It is a term that summarizes different arguments, advocating that fine art and culture would somewhen contribute in an urban environs to:

-

Economic revenues

-

Strong identity and cultural vibrancy

-

Urban quality and liveability

These intangible avails are gradually included into the Smart Cities discourse besides [31]. Thite positions Smart Cities every bit fundamental to homo resource development [32], whereas Han and Hawken discusses innovation and identity triggered by them [33]. The implementation of cultural projects or activities will not only imply the cosmos of lateral local economical revenues [34], but too create incomes generated by tourism [35] and attract a creative class that will push urban economies into a post-industrial lodge [36,37]. In a period of cognition economy [38], the production of ideas rather than the product of goods creates wealth. Cognition production is dynamic, seeking innovation in club to remain competitive. The people, who are able to drive the innovation, are regarded every bit creative people and they constitute the artistic class. Richard Florida positions the idea of the "creative course" that transforms cities undergoing the transition to a post-industrial economy. Past creative class, he refers to a broad range of creative professionals that seek quality of life, tolerance, and creative vibes in cities (the three "Ts" are talent, tolerance and technology) [36,39]. In a global competition among cities, municipalities should back the arts and civilization, precisely to feed the creative atmosphere to attract the creative class [40]. In this context, technology and human capital work together to advance lodge [41], implying that "'smart applied science' advance(s) 'smart mobility', 'smart surroundings', 'smart people', 'smart economy', smart living' and 'smart governance'" [42].

Both the art tourism, the local conscript, and the creative course consider art and culture equally a article, carrying contradictions and limits. For instance, the artistic occupations explored by Florida include lawyers, scientists, managerial and business professionals as well equally artistic people. These professional groups can exist attracted by consumption strategies of art and culture, regarded mainly as entertainment, unlikely to do good artists per se [43].

Civilization and art are too role of an urban calendar, every bit they are able to impact people'due south identity and quality of life. Cultural approaches haven been seen as tools for urban regeneration [44]. Through the implementation of flagship cultural projects, public spaces, and urban landscaping, information technology is possible to develop a shared urban vision or national prototype. These projects can contribute to building a shared character and a distinct identity for the place. In the case of Singapore's city-state, they can be mobilized to the level of nation-building. In the context of Singapore, Calder provides an overview of Singapore'due south socio-economic solutions equally a country, exploring national policies relative to smart states. According to Calder, Singapore is providing "social protection, facilitating economical development, conduction of foreign relations through a minimalist and enabling governance". Singapore'south ongoing urban transformation is fueled by revolutionary ICT developments and supported past a holistic planning process [45]. Singapore makes a item case. Precisely considering of its small territory, city, land, and nation coincide. Due to its lean government arrangement, the deployment of smart metropolis technologies and policies is achieved at a fast stride. Distinct places non just develop the potential to depict people and serve as a driver to develop tourism industry and attraction of inwards investment [46], only the presence of distinct places also near likely increases the interaction intensity between people and the urban surround, improving people'southward quality of life and urban quality.

From a planning perspective, the Artistic City argues for new modes of governance. Starting from the assumption that contemporary governance arrangements inhabit innovative initiatives, new modes of governance should have a double inventiveness, in terms of its potential to both foster inventiveness in social and economic dynamics and creatively transform its own capacities [47]. Flexibility and the power to transform and to suit to multiples needs are fundamental aspects necessary to respond in multiple ways to the metropolis creative dynamism [47].

i.four. Art, Cultural, and Artistic Industries

There are different cultural models that define and describe the relation between art, cultural, and creative industries. Co-ordinate to KEA'south model referring to Europe, they are as follows [48]:

The cultural sector, including:

-

In the non-industrial sectors producing non-reproducible appurtenances and services aimed at being consumed on the spot (a concert, an art off-white, an exhibition). These are the arts field (visual arts including paintings, sculpture, craft, photography; the arts and antique markets; performing arts including opera, orchestra, theatre, dance, circus; and heritage including museums, heritage sites, archaeological sites, libraries, and archives).

-

In the industrial sectors producing cultural products aimed at mass reproduction, mass broadcasting and exports (e.g., a volume, a picture show, a sound recording). These are cultural industries including film and video, video games, dissemination, music, book and press publishing.

The creative sector:

-

In the creative sectors, culture becomes a creative input in the production of non-cultural goods. It includes activities such every bit design (way design, interior blueprint, and product pattern), compages, and ad. Cultural resources are often considered intermediate consumption appurtenances for production processes in non-cultural sectors, and thereby seen equally a source of innovation. In this sense, the non-industrial cultural sectors and the cultural industries support the development of other fields such as cultural tourism and, maybe more importantly, information and communication applied science (ICT) industries, revealing the links between culture, creativity, and innovation.

ane.five. What Makes Singapore a Artistic City?

Singapore adopted a framework to back up art production in urban settings. Singapore's first contribution in cultural planning was the Report of the Advisory Quango on Culture and the Arts (ACCA) [49]. Supporting art was seen every bit necessary to develop national identity, societal bond, individual benefit, quality of life, and mass tourism. The Written report of the Advisory Council on Civilization and the Arts mainly lamented the lack of physical infrastructure to support the arts in Singapore. The reaction was the evolution of the National Museum and more space given to the National Library, but also programs such equally the Fine art Housing Scheme.

The Renaissance Metropolis 2.0 plan was appear in 2001 [50]. This plan shifts the attention from the development of the hardware (facilities) to the software (capacity building, audience development). It likewise claims the need to merge fine art with entertainment, mixing the agencies related to commercial and non-commercial art and adopting a creative industries perspective, with creative industries benefitting from the presence of cadre art. The following planning frameworks by the Urban Redevelopment Authority thus included tangible urban planning measures. The Center for Liveable Cities in Singapore retraced the path toward Singapore as a "City of Culture" [51].

Singapore joined the UNESCO Creative Cities Network and focused on "blueprint" in 2015. The focus on design indicated that creative industries were understood in the wider sense of Florida (2002) and KEA (2006) and were meant to support the rise of industry 4.0 and economic diversification. According to the DesignSingapore Council: "Blueprint remains the key driver of the local creative economy past contributing annually about $2.13 one thousand thousand to the citystate's GDP, with an estimated 5,500 active pattern enterprises employing up to 29,000 people" [52]. Singapore equally a Artistic City is presented in Table 1.

one.vi. Convergence of Smart Cities and Creative Cities

The white paper by the Good Working Group on Smart City Application and Requirements describing the Smart City included "Smart People", referring to people with a high level of qualification, affinity to life-long learning, social and ethnic plurality, flexibility, creativity, cosmopolitanism and open-mindedness, and inclined to participate in public life [16]. Participation and the Smart Urban center are fundamental to van Waart [72]. The Smart People have much analogousness, already in the definition, with the artistic class supported by Florida [36]. According to the white paper, these people capeesh Smart Living that includes cultural facilities and tourism attractions. Both planning paradigms, in the evolution of their concepts, point in a similar direction. We argue that these two positions—of Smart Cities and Artistic Cities—converge as they both consider the quality of life of people, or more specifically, the "urban quality", "open governance processes", and "cultural life and participation" equally primal components. We could actually consider these three points as the intersection of the two planning paradigms, designing a common path of deportment.

As discussed, the Smart City moved abroad from a technologically oriented goal, but it is still technologically intensive in its methods, meaning that it supports processes which are enhanced by technology. The nearly innovative technologies that tin support planning and conclusion-making, or revolutionize the manner nosotros live and refer to cities are "big data", "model and simulation", "bogus intelligence", "blockchains", "automation or robotics", and "Cyberspace of things or information technologies". We thus see a clear overlap of smart technologies on the one hand and creative economies on the other [73]. The intersection gives space for an emergent Smart-Cultural City with Smart-Cultural Clusters and Smart-Cultural Actors in Singapore.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Domain Definition

This article identifies actors in the Smart-Cultural Cities discourse in Singapore. The actors are selected from a database collected past the Singapore-ETH Centre (SEC) drawing upon shared contacts of the institutional partners of the Campus for Inquiry Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) endorsed by the National Enquiry Foundation (NRF) of Singapore. Given the tight network of governmental, academic, entrepreneurial, and artistic actors in Singapore, this database is considered the most representative available. All actors are anonymized. The field of actors on the topic of smart cities has been divided into the post-obit four sectors deemed meaning every bit they overlap and potentially converge on the topic of Smart-Cultural Cities discourse in Singapore:

-

Authorities

-

Academia

-

Manufacture

-

Creative person

The actors are selected according to their position toward the field of Smart-Cultural Cities. To do and so, we transform the domain of the problem into a network and analyze the network using a clustering optimization algorithm. The advantages of this methodology can be summarized every bit follows:

-

Different other clustering methodologies, the number of clusters is not required as input. Rather, information technology is plant automatically when solving the problem.

-

The problem can be solved exactly. Many other popular clustering bug are oft solved heuristically (e.thou., K-means [74]).

-

This methodology allows a better visualization and interpretation of the results. As a matter of fact, regardless of the number of actors and domains, visualization is e'er possible, whereas methods similar K-means allows for visualization only upwardly to dimension 3. Other methods that reduce dimension (east.g., principal component analysis (PCA)) may allow visualization but, due to the change of domain, the interpretation could testify to be hard.

These selected actors expand the conventional field of their operation toward a larger discourse on science, technology and policy in the urban center (e.g., Smart City). We included only those actors who direct address a wider definition of Smart City, which looks at the urban quality, governance, and cultural production, through the use of technology (information applied science, artificial intelligence, information, etc.). The list of actors has undergone an optimization process as described below.

The Action describes the way of engagement of the actors within the Smart-Cultural Cities discourse. These forms of engagement are Discuss, Share, Criticize, Contribute, and Make. The Goals describe the larger topics that the actors want to contribute to within the Smart-Cultural discourse. These goals are Urban Quality of Life, Participation and Governance, support of Cultural Production. The Methods describe the technological tools, domain expertise, and approaches chosen by the actors relative to the Smart-Cultural soapbox.

The choice of Actors prioritizes the Bureau these actors exercise in their field in the calorie-free of the Smart-Cultural transition.

-

Authorities: As the regulating and legislating bodies that govern the processes of urban transformation, this group engages with data, new media, and digital technology to cope with the irresolute duties of public service, to adjust to demands for data transparency and participation.

-

Academia: Equally the scientific community that drives progress and innovation, this group uses information, new media, and technology to gain new insights and generate knowledge.

-

Industry: As the applicators that transform economies, this grouping mobilizes data, new media, and technology to disrupt conventional business models and to introduce.

-

Artist: As the disquisitional inquirers and experimenters, this group explores information, new media, and technology to comment and to create.

ii.ii. Bipartite Networks

The problem under study is characterized by two groups of entities, namely, the actors and their corresponding domain. This scenario tin can be modeled by means of a bipartite network, that is, a graph which consists of 2 prepare of nodes, called red (R) and blue (B), such that edges can merely link an element of R to one of B. In our instance, red nodes represent actors, blue nodes represent domains, and edges connect each actor with their domains. This representation of the trouble allows us to utilise a network analysis technique which can, by exploiting the construction of the network, identify groups of actors and domains that are densely connected. Those groups are called clusters and are identified by solving an optimization problem. More precisely, afterward the resolution, nosotros get the values of the variables which tell usa the cluster each node of the network belongs to.

Given a bipartite network, one mode to place clusters of nodes densely connected is to employ the bipartite modularity metric introduced past Barber [75]. The bipartite modularity value of a cluster represents the difference between the fraction of edges in the cluster and the expected number of such edges in a random network whose nodes take the aforementioned degree distribution. Hence, a big value of bipartite modularity for a cluster means that the relationship between its nodes is strong. As each cluster in the network tin can be characterized by its corresponding bipartite modularity value, the thought is to assign nodes to clusters in order to maximize the sum of bipartite modularity of all the clusters. This yield an optimization problem, whose model is presented here as Equation (1):

where

is the whole set of nodes (i.due east., red followed by blue nodes), m is the full number of edges of the graph,

is a value equal to one when nodes i and j are connected by an edge, 0 otherwise, and

is the degree of node i (i.east., the number of nodes connected to i). Apropos the variables of the problem,

is a binary variable equal to i if nodes i and j are in the aforementioned cluster, 0 otherwise. The objective function to maximize is the bipartite modularity, and the constraints of the problem impose that if nodes i and j vest to the same cluster, and nodes j and l belong to the same cluster, then nodes i and l also belong to the same cluster.

Since Problem (1) can be considered an integer linear programming (ILP) one—an optimization problem where in that location are integer variables and linear constraints/objective part—it can exist solved with a country-of-the-art software for ILP problems like CPLEX [76]. However, as the bipartite modularity maximization problem is NP-hard [77], when the size of the network is too large, finding the optimal solution may bear witness to exist computationally challenging. Hence, heuristics should be used to observe adept quality solutions in a reasonable amount of time (run into, for instance, [78,79,eighty]). For the purpose of analyzing the Smart-Cultural Urban center of Singapore, we do non need to employ heuristics because the size of the network nether study is not too big. The solution of the ILP problem provides the optimal values of the variables

, namely, the data indicating whether each pair of nodes belongs to the same cluster, and this information can be used to identify the clusters. Note that unlike other clustering methods such as Chiliad-means, the bipartite modularity maximization does not require as input the number of clusters.

Thirty actors from 4 professional groups or sectors have been evaluated for eleven domains of expertise. The graph network depends on the initial set up-upward and how we attributed the domains of expertise to the professional groups. Each histrion from the four professional groups is linked to the domains applicative (see Table 2 below). It is important to note that this attribution is a qualitative judgement, identical to the selection of the actors. Information technology is further noted that even though the sample size is minor, the methodology is based on solving a deterministic optimization trouble rather than computing a statistic which needs a large sample size to exist meaning. Clusters tin be identified even when a network size is small; for example, a complete graph where each node is connected to the others is ordinarily identified as a cluster past various community detection methodologies regardless of the dimension. The resulting graph strength (i.due east., the optimal bipartite modularity value) gives an indication on the structure (or randomness) of the clusters. The graph strength value that is a measure of how far this graph network differs from a random graph was at 0.23, indicating a relatively structured graph. This underlines that the initialization was sensible and that the results yielded meaningful insights.

3. Results

3.ane. Emergent Clusters

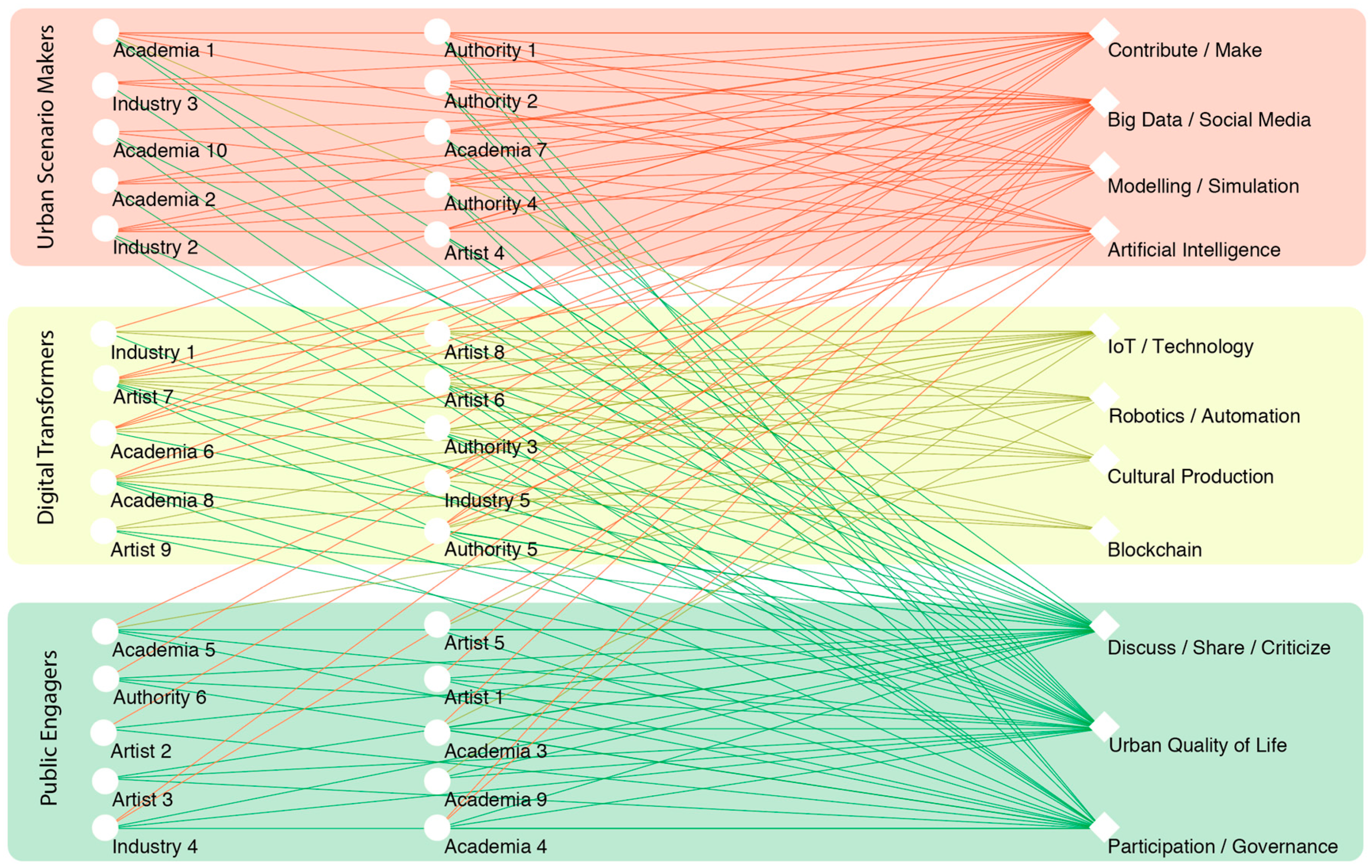

The algorithmic optimization of the graph shows that three distinct emergent clusters appear (run into Figure 1). These clusters mix the members of the four professional groups and are thus not a re-iteration of these groups. Annotation that the optimal number of clusters is not a parameter to be provided, rather it is constitute automatically by solving the optimization problem. The connections between the two sides of the graph from left to right relate actors to domains, that is, they clarify the chief connectedness and within clusters. The three clusters include ten actors each. The distribution of the dissimilar professional groups in the 3 clusters is quite counterbalanced.

The first cluster is mainly defined past the use of applied science (Fields/Methods) and the Action, as it includes 50% of the actors dealing with Big Data, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Modelling and Simulation and xc% produce tools and services, rather than studying them. The combination of the iv domains describe a clear method to automatically generate and assess urban scenarios. The first cluster volition be called Urban Scenario Makers.

The 2nd cluster is defined past a common goal as it includes lxx% of the actors directly addressing the demand to enrich cultural production in cities, using mixed technologies (100% of blockchains, 85% of robotics, 83% of IoT). The second cluster will exist called Digital Cultural Transformers.

The third cluster is also mainly divers past a common goal and the type of Activity, as it includes 50% of the actors dealing with participation or advocating for a different type of governance. Even in this case there is a articulate methodology: these actors mainly discuss to enhance awareness and produce more than participation with respect to the smart-cultural city. The third cluster will be chosen Public Engagers.

3.2. Cluster Interrelations

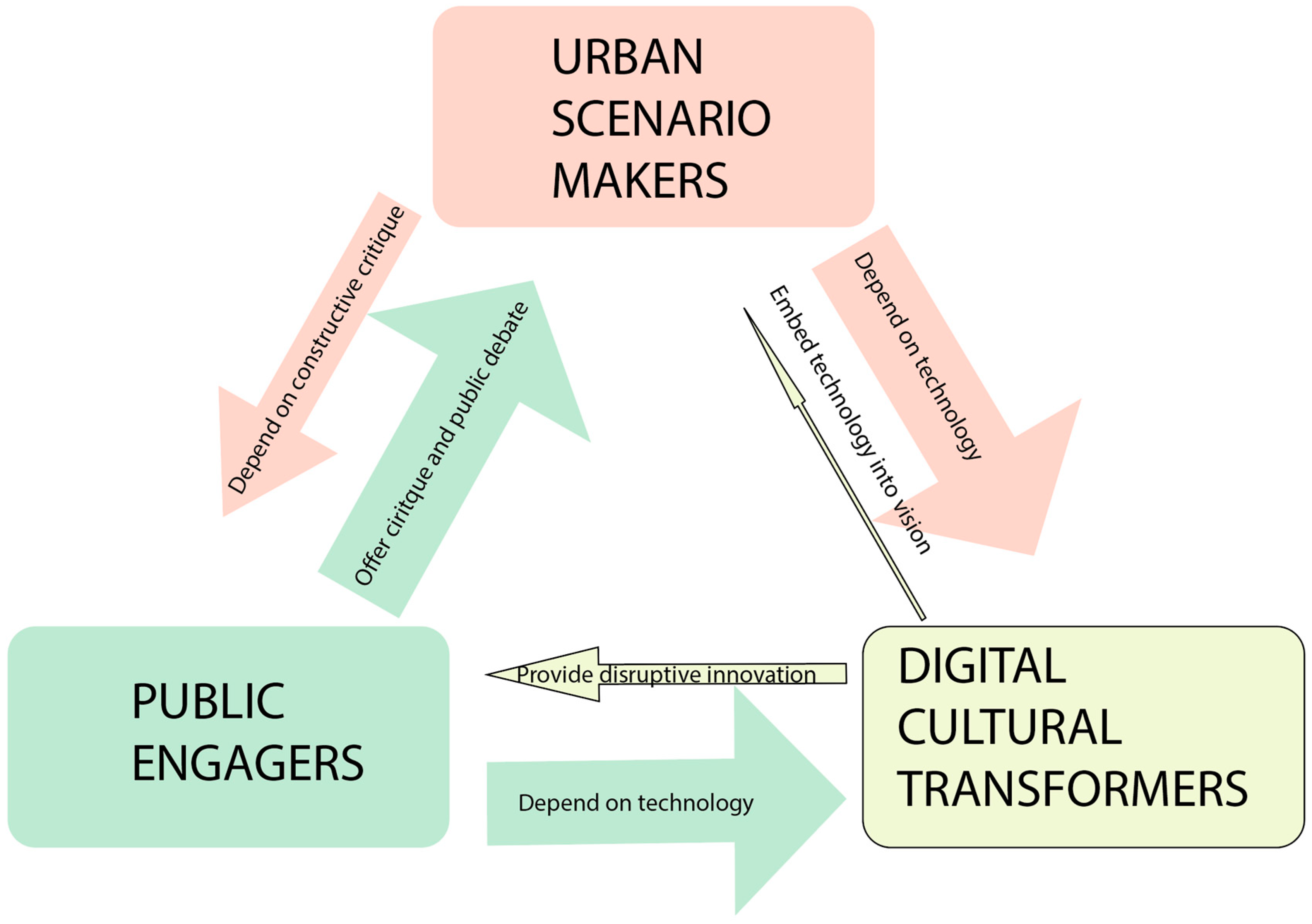

Further engagement areas open up in shut examination of the graph structure. The graph secondary connections from right to left chronicle domains to actors, that is, they analyze the supportive links across clusters (see Effigy two). These "weak" links indicate potential areas for fruitful engagement discussed in the conclusion section. Finally, we describe the iii emergent clusters in particular by examining the commonalities of the actors that make upwards the cluster. The three clusters are interdependent and their links and interdependencies deserve closer attention.

4. Discussion

4.ane. Answering the Research Questions

The findings bear witness that smart technologies indeed contribute and increasingly drive Smart Cities and creative economies in Singapore. The proposed methodology also allows us to analyze the histrion database and formalize the relationships amid actors of Smart-Cultural Cities. We identified meaningful groups of actors within the Smart-Cultural City of Singapore as shown in the table. This commodity also demonstrates the presence of actors in Singapore who belong to, back up, and talk over the artistic fields and industries in Singapore and thereby contribute to the evolution of the Smart-Cultural City.

4.ii. Interpretation of Clusters

Urban Scenario Makers navigate multiple urban scales and create scenarios in a pro-active mode. The combination of applied science including big information and AI as well every bit local and cultural insight allows Urban Scenario Makers to test decisions and the effects of decisions. For example: What is the issue of a new road on traffic, the neighborhood, and liveability? Existent-time traffic information allows us to create realistic models, which tin then react to the new element, highlighting limits and potentials of urban development. Urban Scenario Makers expect at all aspects of urban life: the quality of public space, the diversity of artistic neighborhoods, gentrification processes. The Urban Scenario Makers test the city of the future before it happens. The Urban Scenario Makers depend on the Digital Cultural Transformers for disruptive new technologies and applications and on the Public Engagers to critique and balance their work.

The Digital Cultural Transformers await at the transformation of our life introduced past new technologies, in particular the manner we produce, swallow, and broadcast art and culture or the way nosotros experience public spaces, or the way nosotros see, swallow, and overall approximate the urban quality of our cities. The Digital Cultural Transformers not only talk over what is already happening and what most likely will happen, but they too propose and produce new technologies and new applications of existing engineering to ameliorate and have an touch on all those aspects of our life. Their innovations yield confusing potential and needs to be discussed broadly past the Public Engagers. At the same time, they depict from the visions developed past the Urban Scenario Makers to frame their transformation projects.

The Public Engagers focus on public contend and discussion. They lift themselves to a higher place the Digital Cultural Transformers every bit they oftentimes lack the tools and technology to actually transform and instead appoint the public. Beingness disquisitional and reactive, the Public Engagers shy away from developing scenarios, yet depend on those proposed by the Urban Scenario Makers.

4.iii. Activating the Smart-Cultural City of Singapore

This article investigates the emergent intersection and convergence of Smart Cities and Creative Cities that emerge with the availability of social media information, technology, and the shifting fashion of cultural production forming a new nexus of Smart-Cultural Cities. The article identifies three emergent clusters in the Smart-Cultural Cities discourse for Singapore – Urban Scenario Makers, Digital Cultural Transformers, Public Engagers. These clusters nowadays potential areas for meaningful and strategic engagement within the Smart-Cultural City of Singapore for future urban planning and cultural production as an expansion of the Smart City as well as the Creative Urban center.

Each of these clusters has a counterbalanced contribution of the dissimilar professional groups and actors. Yet, those groups and actors might not know of each other's work and rarely come together in real life. Fifty-fifty if they share similar goals, type of deportment, and methods, they unremarkably work in parallel addressing similar issues with different perspectives.

Very few artists are found in the "Urban Scenario Makers" cluster. As a consequence, there is trivial critical discussion about scenarios and visions (e.g., a strong prevailing techno-naïve mental attitude). The "Urban Scenario Makers" cluster have no links to "applied" technology in the digital transformation group. Their tools are data and simulation. In return, they do not engage with tangible technologies, still.

The "'Public Engagers" cluster discusses primarily the consequences of shifting public engagement through engineering and culture without actively developing technology or cultural production.

The "Digital Cultural Transformers" cluster is the nigh counterbalanced of the iii, every bit it includes actors who both talk over and make, they come from all the dissimilar professional groups, and they normally directly accost the cultural production in cities with different and emerging technologies. This is the near "convergent" cluster in the sense of the Smart-Cultural Cities proposed hither with a high potential of creative advancement of the discourse as they have many commonalities.

4.four. Outlook: Farther Research and a New Tool forDdigital Humanities and Denizen-Centered Smart City Research

The bipartite graph method was tested as a new qualitative method for digital humanities. It allows the states to reveal underlying structures in a network. Analysis and interpretation of the resulting segmentation of the network give insights into clusters and gaps. Being able to identify these clusters and their dynamic interrelation is essential to develop a denizen-centered Smart Urban center research. This allows u.s.a. to activate previously invisible linkages among actors and leverage synergies in borough participation. The findings hint at further research questions to be answered in the future, for example: Are information-rich environments necessarily supporting artistic industries? How does research in disruptive technologies influence the number and impact of artistic industries? Do e-governance processes influence cultural product? If and then, in what way? The geographic case study of Singapore and the particular thematic intersection of Smart-Cultural Cities can be translated to other cities, regions, and nations.

Writer Contributions

Conceptualization, A.v.R. and Fifty.T.; methodology, A.v.R. and A.C.; software, A.C.; validation, A.C.; formal analysis, A.5.R. and Fifty.T.; resources, Fifty.T.; writing—original typhoon grooming, A.v.R., 50.T., and A.C.; visualization, A.C. and A.5.R.; project administration, A.v.R.; funding acquisition, A.five.R.

Funding

The research was conducted at the Futurity Cities Laboratory at the Singapore-ETH Heart, which was established collaboratively between ETH Zurich and Singapore's National Research Foundation (FI 370074016) under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise program. Funding for the inquiry on Smart and Cultural Cities came from the Goethe Institut, the Federal Commonwealth of Federal republic of germany'south cultural establish, in Singapore.

Conflicts of Involvement

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or estimation of information; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kummitha, R.G.R.; Crutzen, N. How do we understand smart cities? An evolutionary perspective. Cities 2017, 67, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchia, A. Smart and Digital City: A Systematic Literature Review. In Smart City; Dameri, R.P., Rosenthal-Sabroux, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerlandm, 2014; pp. thirteen–43. ISBN 978-3-319-06159-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhlandt, R.W.S. The governance of smart cities: A systematic literature review. Cities 2018, 81, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, Due east.P.; Hinnig, M.P.F.; da Costa, E.M.; Marques, J.S.; Bastos, R.C.; Yigitcanlar, T. Sustainable development of smart cities: A systematic review of the literature. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Circuitous. 2017, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; del Pobil, A.; Kwon, S. The Role of Net of Things (IoT) in Smart Cities: Applied science Roadmap-oriented Approaches. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuhadar, 50.; Thrasher, Eastward.; Marklin, S.; de Pablos, P.O. The adjacent wave of innovation—Review of smart cities intelligent operation systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Heims, South.J. The Cybernetics Group; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, United states of america, 1991; ISBN 978-0-262-08200-six. [Google Scholar]

- Commission to the Quango; European Parliament; European Economic and Social Committee. Commission of the Regions European Strategic Free energy Applied science Plan (SET-Programme): Towards a Depression Carbon Time to come; Brussels, Belgium, 2007. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/free energy/en/topics/engineering-and-innovation/strategic-energy-technology-programme (accessed on 6 Dec 2018).

- European Commission. Strategic Energy Technology Plan; European Committee: Brussels, Kingdom of belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deakin, M.; Al Waer, H. From intelligent to smart cities. Intell. Build. Int. 2011, 3, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Greenish Version]

- Falconer, F.; Mitchel, S. Smart Metropolis Framework: A Systematic Process for Enabling Smart + Connected Communities; Cisco: San Jose, CA, U.s.a., 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pollalis, Southward.N. (Ed.) Challenges in infrastructure planning and implementation. In Planning Sustainable Cities: An Infrastructure-Based Approach; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-18842-6. [Google Scholar]

- Infrastructure & Cities—Sustainable Cities—Siemens. Available online: http://w3.siemens.com/topics/global/en/sustainable-cities/Pages/dwelling house.aspx (accessed on 21 May 2014).

- Hollands, R.K. Will the real smart city delight stand up?: Intelligent, progressive or entrepreneurial? City 2008, 12, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffinger, R. Smart Cities: Ranking of European Medium-Sized Cities; Centre of Regional Science: Vienna, UT, Us, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Net!Works European Technology Platform; Correia, 50.One thousand.; Wünstel, K. Smart Cities Applications and Requirements. 2011. Available online: https://grow.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/White_Paper_Smart_Cities_Applications.pdf (accessed on vi December 2018).

- Department of Business concern Innovation & Skills. Smart Cities: Background Newspaper; Department of Business Innovation & Skills: London, United kingdom, 2013.

- Bundesverband Smart Cities eastward.V. Available online: https://www.bundesverband-smart-urban center.de (accessed on six December 2018).

- Centre for Cities. Available online: http://www.centreforcities.org/about/ (accessed on 6 Dec 2018).

- Layne, K.; Lee, J. Developing fully functional E-government: A four phase model. Gov. Inf. Q. 2001, eighteen, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechant, P.; Walravens, N. E-Government and Smart Cities: Theoretical Reflections and Case Studies. Med. Commun. 2018, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London Schoolhouse of Economic science LSE Cities Plan. Bachelor online: www.lse.ac.uk/LSE-Cities (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Goldsmith, S.; Crawford, S. The Responsive City: Engaging Communities through Data-Smart Governance; Jossey-Bass, a Wiley Brand: San Francisco, CA, The states, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-91090-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hereafter Cities Laboratory. ETH Singapore Eye Responsive Cities. Bachelor online: www.fcl.ethz.ch (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Goldsmith, South. Social Media's Place in Information-Smart Governance. Information-Smart City Solut. 2016. Available online: https://datasmart.ash.harvard.edu/news/article/social-medias-place-in-information-smart-governance-837 (accessed on half dozen December 2018).

- Tomarchio, 50. Mapping human being landscapes in Muscat, Oman, with Social Media Data. In Arab Gulf Cities in Transition: Space, Politics and Lodge; Cummings, V., von Richthofen, A., Babar, Z., Eds.; ETH Research Collection: Zürich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, L. How Smart City Barcelona Brought the Internet of Things to Life. Data-Smart Metropolis Solut. 2016. Available online: https://datasmart.ash.harvard.edu/news/commodity/how-smart-metropolis-barcelona-brought-the-internet-of-things-to-life-789 (accessed on 6 Dec 2018).

- Bakıcı, T.; Almirall, E.; Wareham, J. A Smart City Initiative: The Case of Barcelona. J. Knowl. Econ. 2013, 4, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technology and the City: Foundation for a Smart Nation; Urban Systems Studies; Centre for Liveable Cities Singapore: Singapore, 2018; ISBN 978-981-11-7796-5.

- Many Smart Ideas—One Smart Nation. Bachelor online: https://world wide web.scl.org/manufactures/3390-many-smart-cities-i-smart-nation-singapore-due south-smart-nation-vision (accessed on 6 Dec 2018).

- Neirotti, P.; De Marco, A.; Cagliano, A.C.; Mangano, G.; Scorrano, F. Current trends in Smart Metropolis initiatives: Some stylised facts. Cities 2014, 38, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Light-green Version]

- Thite, M. Smart cities: Implications of urban planning for human resource development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2011, 14, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hawken, S. Introduction: Innovation and identity in adjacent-generation smart cities. Metropolis Cult. Soc. 2018, 12, i–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myerscough, J. The Economical Importance of the Arts in Britain; PSI Research Written report; Policy Studies Institute: London, UK, 1988; ISBN 978-0-85374-354-5. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators; Reprinted; Comedia: Near Stroud, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-1-85383-613-8. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R.Fifty. The Rise of the Creative Course: And How Information technology'due south Transforming Piece of work, Leisure, Customs and Everyday Life; Bones Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-465-02477-three. [Google Scholar]

- You, H.; Bie, C. Creative grade agglomeration across time and infinite in knowledge city: Determinants and their relative importance. Habitat Int. 2017, threescore, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P.F. The Age of Discontinuity: Guidelines to Our Changing Society; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1969; ISBN 978-1-4831-6542-iv. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R.50. Cities and the Creative Course; Routledge: New York, NY, United states of america; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan, C. Let's Inspect Bohemia: A Review of Richard Florida's 'Artistic Class' Thesis and Its Affect on Urban Policy: Let'southward inspect Bohemia. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, G. Smart cities: A conjuncture of four forces. Cities 2015, 47, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C.; Nijkamp, P. Smart Cities in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J. Struggling with the Creative Class. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2005, 29, 740–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Light-green Version]

- Cangelli, Due east. An up-close look at Urban Regeneration. Cultural approaches and applied strategies for the rebirth of cities. TECHNE J. Technol. Arch. Environ. 2015, ane, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, 1000.E. Singapore: Smart City, Smart Land; Brookings Establishment Press: Washington, DC, Usa, 2017; ISBN 978-0-8157-2948-eight. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, M.; Bianchini, F. (Eds.) Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration: The West European Experience; Manchester Univ. Press: Manchester, UK, 1993; ISBN 978-0-7190-4576-9. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Creativity and urban governance. Policy Stud. 2004, 25, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KEA. The Economy of Culture in Europe. 2006. Bachelor online: http://world wide web.keanet.eu/ecoculture/executive_summary_en.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Council on Culture and the Arts. Study on Informational Quango on Civilisation and the Arts; Quango on Civilisation and the Arts: Singapore, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Information and the Arts. Renaissance City ii.0; Ministry of Information and the Arts: Singapore, 2001.

- Wong, M.; Koh, M.; Araib, South. A Urban center of Culture: Planning for the Arts; Wu Wei, N., Ed.; Urban Systems Studies; Centre for Liveable Cities: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Artistic Cities Network—Singapore. Bachelor online: https://en.unesco.org/artistic-cities/singapore (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Chiu, Y.-H. Evaluation of the Policy of the Creative Industry for Urban Development. Sustainability 2017, nine, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negruşa, A.; Toader, V.; Rus, R.; Cosma, South. Study of Perceptions on Cultural Events' Sustainability. Sustainability 2016, viii, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbrun, J.; Gray, C.M. The Economics of Art and Culture, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Printing: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-521-63150-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry building of Culture, Community and Youth. Singapore Cultural Statistics; Ministry building of Culture, Community and Youth: Singapore, 2017.

- Degen, K.; García, Grand. The Transformation of the 'Barcelona Model': An Analysis of Culture, Urban Regeneration and Governance: The cultural transformation of the 'Barcelona model'. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 1022–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, A. Fine art tourism: A new field for tourist studies. Tour. Stud. 2018, eighteen, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Dai, D. Creative Form Concentrations in Shanghai, China: What is the Office of Neighborhood Social Tolerance and Life Quality Supportive Weather condition? Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, T.; Janeba, E. City competition for the artistic form. J. Cult. Econ. 2016, 40, 413–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodhouse, S. Cultural Quarters Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; Intellect: Bristol, United kingdom, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tavano Blessi, 1000.; Tremblay, D.-Grand.; Sandri, 1000.; Pilati, T. New trajectories in urban regeneration processes: Cultural capital letter as source of human and social capital aggregating—Evidence from the case of Tohu in Montreal. Cities 2012, 29, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, 1000.; Fung, A.; Moran, A. New Television, Globalisation, and the East Asian Cultural Imagination; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, Cathay, 2007; ISBN 978-962-209-820-six. [Google Scholar]

- National Art Council Review of National Art Council's Art Housing Scheme 2010. Available online: https://www.nac.gov.sg/dam/jcr:fa540138-43a9-46be-8e81-55a386a4831a (accessed on six December 2018).

- National Art Council Framework for the Fine art Space. Bachelor online: https://www.nac.gov.sg/whatwedo/back up/arts-spaces/framework-for-arts-spaces.html (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Yarker, Due south. Tangential attachments: Towards a more nuanced understanding of the impacts of cultural urban regeneration on local identities. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 3421–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Miles, S.; Stark, P. Culture-led urban regeneration and the revitalisaton of identities in Newcastle, Gasteshead and the North E of England. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2004, 10, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Redevelopment Say-so Community and Sports Facilities Scheme 2003. Bachelor online: https://www.ncss.gov.sg/GatewayPages/Social-Service-Organisations/Funding,-Schemes-and-Common-Services/Benefit-Schemes/Community-Sports-Facilities-Scheme (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- National Art Council Art Attain. Available online: https://www.nac.gov.sg/whatwedo/engagement/artsforall/art-attain.html (accessed on vi December 2018).

- National Art Council Population Survey on the Arts 2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.nac.gov.sg/whatwedo/support/research/Research-Chief-Page/Arts-Statistics-and-Studies/Participation-and-Attendance/population-survey.html (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- National Art Council the Study on Fine art and Culture strategic Review 2012. Available online: https://www.nac.gov.sg/aboutus/arts-civilization-strategic-review.html (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Van Waart, P.; Mulder, I.; de Bont, C. A Participatory Approach for Envisioning a Smart Metropolis. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2016, 34, 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Richthofen, A.; Tomarchio, L. Knowledge Map: Smart/Cultural City Singapore; Singapore ETH Centre & Goethe Establish Singapore: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen, J. Some Methods for Classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, U.s., 1967; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, One thousand.J. Modularity and customs detection in bipartite networks. Phys. Rev. Eastward 2007, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- IBM ILOG CPLEX Optimization Studio CPLEX User's Manual. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/knowledgecenter/SSSA5P_12.6.2/ilog.odms.studio.assist/pdf/usrcplex.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Miyauchi, A.; Sukegawa, N. Maximizing Barber's bipartite modularity is also difficult. Optim. Lett. 2015, 9, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Hansen, P. A locally optimal hierarchical divisive heuristic for bipartite modularity maximization. Optim. Lett. 2014, 8, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Murata, T. Graduate School of Information science and Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro, Tokyo 152-8552, Japan An Efficient Algorithm for Optimizing Bipartite Modularity in Bipartite Networks. J. Adv. Comput. Intell. Intell. Inform. 2010, 14, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauset, A.; Newman, M.E.J.; Moore, C. Finding community construction in very large networks. Phys. Rev. E 2004, seventy, 066111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Light-green Version]

Figure i. Bipartite graph and clusters of selected Smart-Cultural Cities discourse actors and domains in Singapore.

Effigy 1. Bipartite graph and clusters of selected Smart-Cultural Cities discourse actors and domains in Singapore.

Figure 2. Framework of Smart-Cultural Thespian clusters in Singapore and their interdependencies according to the number of connections.

Figure 2. Framework of Smart-Cultural Actor clusters in Singapore and their interdependencies according to the number of connections.

Table i. Singapore every bit a Creative Metropolis, Land, and Nation.

Table ane. Singapore as a Creative Urban center, State, and Nation.

| Goal | Scientific Concept | Evidence of Implementation in Singapore |

|---|---|---|

| Creation of lateral economic revenues generated past the implementation of cultural projects or activities | Myerscough, Liu and Chiu, Negruşa et al., Heilbrun and Gray [34,53,54,55] | Singapore cultural statistics 2015–2017 [56] |

| Income generated by tourism | Landry, Degen and García, Franklin, Heilbrun and Gray [35,55,57,58] | Singapore cultural statistics 2015–2017 [56] |

| Attract a creative class that volition push button urban economies into a post-industrial gild | Florida, Liu and Chiu, Rao and Dai, You and Bie, Buettner and Janeba [36,37,53,59,60] | Singapore cultural statistics 2015–2017 [56] |

| Cluster of cultural activities to produce economic benefits and other benefits, like pools of common knowledge and skills, flexible human being resource, relations of trust, and a sense of common goals | Roodhouse, Tavano Blessi et al., Keane, Fung, and Moran [61,62,63] | Singapore Art Belts in Fine art Housing Scheme (1985), Masterplan of the Borough and Cultural District (1988), Framework for the Arts Spaces (2010) [64,65] |

| Social inclusion and cohesion | Landry, Yarker, Bailey, Miles, and Stark [35,66,67] | Community/Sports Facilities Scheme (CSFS) (2003), Art Reach (2012) [68,69] |

| Shared urban vision or image | Landry, Yarker, Degen and García, Bailey, Miles, and Stark [35,57,66,67] | Implementation of national infrastructures like the National Gallery (2015), etc. |

| Interaction intensity between people and the urban | Landry 2006 [35] | Singapore cultural statistics 2015–2017 [70] |

| Creation of a framework for civilization | Landry 2006 [35] | The Renaissance City Program I-II-Iii (2001-2011), Report on Fine art and Civilisation Strategic Review (2012–2018) [49,71] |

Table ii. The actor–attribution matrix creates the bipartite graph.

Table 2. The role player–attribution matrix creates the bipartite graph.

| Actors | Talk over/Share/Criticize | Contribute/Make | Urban Quality of Life | Participation/Governance | Cultural Production | Big Data/Social Media | Artificial Intelligence | Blockchain | Modelling/Simulation | Internet of Things/Applied science | Robotics/Automation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potency | ane | 10 | 10 | X | Ten | X | Ten | |||||

| Authorisation | 2 | 10 | X | 10 | 10 | Ten | ||||||

| Authority | three | X | Ten | X | Ten | X | ||||||

| Authority | 4 | X | X | 10 | X | X | ||||||

| Potency | v | Ten | X | X | X | Ten | X | X | ||||

| Potency | 6 | X | Ten | X | X | |||||||

| Academia | 1 | X | X | X | 10 | X | Ten | |||||

| Academia | 2 | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Academia | 3 | 10 | 10 | X | X | X | ||||||

| Academia | 4 | 10 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Academia | 5 | Ten | X | X | 10 | X | ||||||

| Academia | 6 | Ten | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Academia | seven | X | 10 | X | X | X | ||||||

| Academia | viii | X | X | 10 | X | 10 | X | Ten | X | |||

| Academia | 9 | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Academia | x | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Manufacture | ane | X | 10 | X | 10 | |||||||

| Industry | two | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||||

| Manufacture | 3 | Ten | Ten | X | X | |||||||

| Manufacture | 4 | X | Ten | 10 | X | X | ||||||

| Industry | 5 | 10 | Ten | X | X | |||||||

| Artist | 1 | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Creative person | 2 | X | X | 10 | ||||||||

| Artist | 3 | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Artist | 4 | 10 | X | Ten | Ten | |||||||

| Artist | 5 | X | X | 10 | ||||||||

| Creative person | 6 | X | X | X | Ten | X | X | 10 | 10 | |||

| Creative person | 7 | X | X | Ten | X | 10 | X | 10 | X | X | X | |

| Creative person | 8 | 10 | X | 10 | 10 | X | ||||||

| Artist | 9 | X | Ten | X | X |

© 2019 past the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open up access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/).

klingbeilnotho1963.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2624-6511/2/1/5/htm

0 Response to "Iot in Arts and Cultur in Camsrt Cities Exmaples"

Publicar un comentario